Startseite

>

Old West Iron Blog: Craftsmanship, Heritage & Hand-Forged Expertise

>

A Brief History of Women in Blacksmithing

A Brief History of Women in Blacksmithing

von/ durch Maddison Nedrow auf Jul 18, 2024It may come as a surprise to some that women have been working as blacksmiths since as early as the middle ages, but the truth is that in family businesses, military forges and factories women have been putting hammer to anvil for centuries!

As a woman founded and women owned blacksmithing shop, we place a lot of value not only on the history of the blacksmithing, but on the historic roles that women played within the trade. Read on to explore the roles and stories of women at the forge.

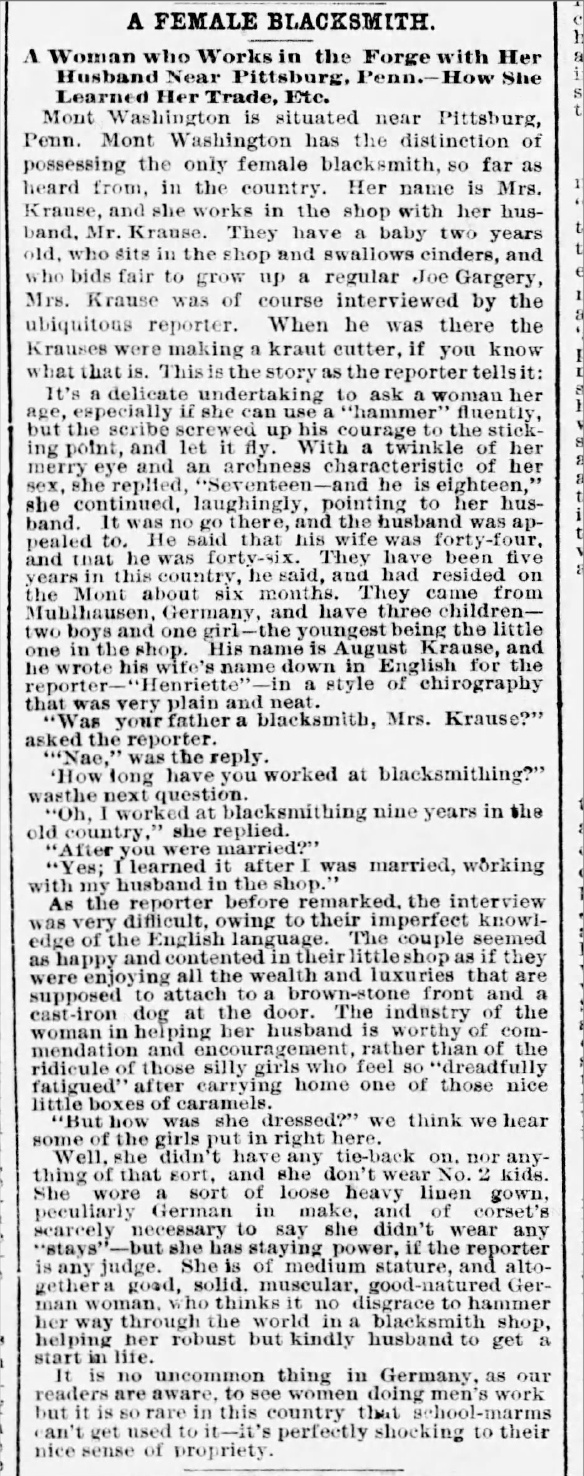

Clipping courtesy of newspapers.com, originally published in the Boston Globe on October 28, 1877. As you may notice, many female blacksmiths in early American history were given space on the pages of newspapers, but they were not always given respect for their craft.

The Path to Blacksmithing

We get it, most of the history books tell of preindustrial women working as housemaids, teachers, or wives and mothers, but it’s fairly uncommon to hear of women working in labor intensive trade jobs before the 1900s. Unfortunately, many people have never heard of old world female blacksmiths before, and it’s fair to have a lot of questions about the process. Let's get into it!

Unlike their male counterparts (read our posts on the history of blacksmithing and the history of modern metals for more information on the process of becoming and working as a blacksmith), female blacksmiths rarely took the expected apprenticeship with a skilled journeyman but rather learned from or alongside their husband, father, or brother and took on the role of assisting them in running their business. Often, women were allowed by their guild to take over the business entirely if their husband or father became unable to work or passed away.

This wasn’t entirely an unusual practice, as all family members were often needed to run a business, whether a farm, market, or smithy. When the head of household passed away, the smithy was usually given to the eldest son in the tradition of most blacksmith guilds but, especially if a family had no sons (or no children at all), it was considered to be perfectly acceptable to pass the business on to a female family member.

Over time, women in the trade (and in most trades, for that matter) became more commonplace in Europe, and in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries women were encouraged to learn a trade in manufacturing. Mainly, these women were employed to make nails and chains, and in many areas female nailers outnumbered their male counterparts for a time.

Woodcut dated to the 1300s depicting

female blacksmith assisting at the forge.

Life at the Forge

So what was life like for these early female blacksmiths? The answer depends a lot on the time and place, but there are a few consistencies throughout the centuries.

Most family members in a blacksmithing family had chores relating to the family business. In most cases, women and children didn’t do the brunt of the work forging and hammering iron, but their work was plenty grueling. One particularly tough chore would have been gathering, splitting, and hauling firewood (sometimes from several miles away), and then firing it to create charcoal, a vital part of the work that takes place at every smithy. Without this wood and charcoal, the business would be unable to operate and would likely fail quickly.

Other family chores included working together to finish the day’s work by shaping, bending, and hammering metal, each taking their turn as needed.

Women who equally shared the responsibility of the smithy or had inherited a business to head did all of the same work that their male counterparts did, but a fact that thoroughly surprises many people (including our blacksmiths here at Old West Iron) is that these women often worked at the hot forge in four or more layers of wool and/or linen clothing.

While the layering may seem excessive and potentially hazardous in such high heat, this was the norm due to a combination of safety concerns and the standards expected of women’s dress in the given time period. Wool and linen are relatively safe fabrics to wear near an open flame, as both are made from organic material and will smolder instead of immediately combusting or melting like many modern fabrics. In fact, wool and linen are considered to be a safer choice even than cotton, which smolders for a much shorter period of time before bursting into flames and burning through.

For example, a woman at the forge in colonial America would most likely wear:

- A bedgown (a loose fitting, wrapped dress that is secured with a pin), usually woolen

- A wool or linen apron

- A wool petticoat

- A wool underpetticoat

- A linen cap

- A linen neckerchief

Each of these layers serves the purpose of reducing the amount of skin exposed to heat, sparks, and flame, protecting her body and head effectively.

Women in Modern Blacksmithing

Today blacksmithing is not as common as it once was, but many skilled artisans have taken up the craft as a hobby, art form, or niche business. Modern blacksmithing is even more open for women to participate in, and many 20th and 21st century women have won awards for their skill and creativity in metal working.

The world of blacksmithing is rich in history, from old world Europe to civil war America, and the untold stories of the women who carried the trade make it all the richer. At Old West Iron, we’re proud to be a part of that heritage and to practice our craft in the traditional way.

Maddison Mellem

Old West Iron

e- purchasing@oldwestiron.com

p- (844) 205-7266

f- (844) 205-7267

https://www.oldwestiron.com/blogs/news

Sources:

Image at top of page is a clipping from the 1918 Pennsylvania Evening Standard. Photo obtained from newspapers.com